At Mzab

An Amazigh society in Algeria

confronting a crisis

Part 2

by Hammou Dabouz

Historical Overview

]]>

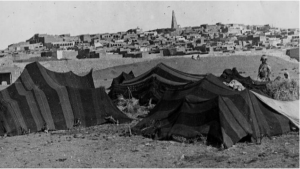

One of the Mzab ancient towns towards the end of the nineteenth century.

When approaching the history of the At Mzab people, we can state that they must be considered as a part of Tamazgha (North Africa). To understand the Mzab today requires us to pick up the threads of a wider history, rich in incidents and lessons learned.

The historical proto-Tumzabt Amazigh people-group living in the Mzab since time immemorial had absorbed Amazigh families who found refuge in this area during various invasions, particularly Roman: these peoples had built pre-Islamic igherman (towns). After the arrival of Islam, and in the seventh century the Christian era, the Amazigh peoples in the area adopted the new religion. A great number of ancient ruins bear witness to the particular presence of pre-Ibadi Amazigh people living there, such as the Talezdit, the Awlawal, the Tmazert, the Bukyaw… This Amazigh population - semi-nomadic we suppose - chiefly survived on livestock breeding and seasonal crops. From the eleventh century the Mzab experienced a golden age and a veritable renaissance, characterized by the Ibadi rituals adopted by the At Mzab people more than 10 centuries ago. This change in mindset and a renewed population growth encouraged the birth of the At Mzab community as it is known today. From that point on five igherman were built on rocky outcrops, namely Ghardaia (Tayerdayt in the Amazigh language), Melika (At-Mlicet), Bounoura (At-Bunur), Al-Atteuf (Tajnint) and Beni-Isguen (At-Izgen). Two further towns – Berriane (Bergan) and Guerrara (Zegrara) are part of the At Mzab territory, although they are situated outside the Mzab valley: the first one 45 km. to the north, the second 110 km. to the north-east.

Life in Society

Mzab towns are organized according to family lines: the lineage (or taddart according to local nomenclature) is a succession of descendants claiming common ancestry: a patrilineal system traced through the males, unlike the structure of Imuhaq (Touaregues) society. The suff (political alliance between groupings) is a nexus of several lines each bringing solidarity and sympathy, an alliance whose nature lacks any institutional aspect and which can be reconfigured at any time. The option of leaving or remaining within the suff depends on one’s lineage. The choice depends on common interests: one is defined by virtue of one’s family and its affiliation. Each town brings together clans that themselves constitute suff alliances. The tribe is structured as a complex pyramid having three levels. The first level comprises the tribal groupings (tiâcirin); based on genealogy they bring together the tiddar (extended families with the same official name and established eponymous ancestry). The fraction or grouping is a foundational administrative entity managed by a representative council.

It has common assets, particularly a central building where it holds its assemblies and conducts wedding celebrations. On the second level, a cluster of fractions constitutes the tribe; this is not essentially a matter of genealogical ancestry but rather a permanent political alliance of fractions and clans. Lastly, the third level: an alliance of tribes under the aegis of the lâezzaben (Ibadhi clerics). This is why E. Masqueray pointed out that the agherm in the Mzab is a second-ranking town which, tripartite in structure, shows striking similarities to the ancient Greek city state.

Today among the modern generation the feeling of belonging to the suff has disappeared. The changes in the life of the region have had a marked impact on social manners and behaviour. New forms of individualized thinking are emerging, and attitudes reflecting more varied patterns of society are increasingly prevalent.

Structures of urban life and architecture

The organization of urban life in the Mzab is Amazigh in its essence and Islamic in its doctrine. In order to understand the influence of the Ibadi ritual it is necessary to examine closely the socio-cultural setting of the Amazigh peoples which have embraced Ibadism. The architecture of Mzab - in its specific environment and responding to strict requirements – is characterized by simplicity. That is why there is a practical hostility to wealth and ostentatious behaviour. Everywhere in the towns of the Mzab communal energies have – over the centuries – been channelled into the building of the seven igherman, the workforce exercising the prime knowledge and practical skills consolidated during the golden age of Tahert, knowledge highly esteemed throughout, and mastered by the At Mzab. It is worthwhile stating that the Mzab forms a continuity of Isedraten (Sedrata), ephemeral and long buried under the desert sands. The founding of the current seven towns (igherman, singular agherm) had been spread over a period of almost seven centuries, with the founding of the final town Bergan towards the end of the seventeenth century. These cities are distinguished by their unique architecture, and the arrangement of religious and profane spaces (mosque and cemetery, dwellings and market-place), interior and exterior planning for the family home as well as for the town itself. The landscape of the Mzab offers a contrasting palette of colours: the pinks and ochres of the hillsides, the greens of the luxuriant oases, the vivid blue of the sky and the pastel blue of the townships where houses are stacked one on top of another.

Interior of a house showing ammas n tiddar (patio), tisefri (living room), tisunan (stairs) and innayen (traditional kitchen).

The typical aɣerm is built on an exposed knoll or hillock, in order to satisfy four fundamental principles:

-

To protect it from any incursion and / or attack from outside, by exploiting the hilly terrain surrounding the aɣerm

-

To protect and to free up land for cultivation.

-

To provide protection from flooding for the urban dwellings and associated activities within the ksar (city, citadel).

-

To ensure the best possible protection against the harsh climate.

Planting the aɣerm with palm trees forms the hub and focus of human activity within a geographical expanse. The key social spaces that the settled population has are:

-

Aɣerm (walled town): a protected habitable space allowing family and social life to thrive.

-

Tijemmiwin (palm tree plantations): place for growing food and for outdoor life.

-

Tindal (cemeteries): space for the dead.

Each aɣerm is organised around three spaces or structural elements, with a network of streets (main street, side street, smaller dead-end alleys): The spaces are:

-

Religious and social centre: the mosque (tamesjida).

-

Private dwelling place (tiddar).

-

Public centre, male and non-religious, the market place (souk).

The siting of each aɣerm meets these requirements, and the facts seem only to emphasise the notion of a desire for isolation and security in the context of oasis life, where the safety and familiarity inside sits in contrast to the hostile and unknown space beyond. As a result of this, Mzab society was forced to provide completely for its very life-giving, substantial needs just as much as for its palm plantations created in the desert. Elsewhere, Ibadism and Tamazight as language and culture make up the dual entity, such that it is difficult to dissociate an umzab (Mozabite) from Ibadism.